This, as you may well guess from the arcane acronym in the Title of this post, this is the inaugural SWASW offering. Now remember: this needs your help to succeed. Read what I've written and post your comments, PLEASE. A book club without discussion is football without the feet.

And now, without further ado...

Hopefully you're mightily familiar with Vonnegut's magic. He's one of my favourite authors that ever put pen to paper, or typewriter, as the case may have been.

Mother Night was his third book, published nearly half a century ago - in good ol' 1961. Meaning, very likely, on this day exactly fifty years ago he was probably working away on this yarn. Or maybe he was taking the day off. It was, after all, a Sunday.

The book is a fictional memoir of an American named Howard Campbell, who grew up in Germany and became one of the greatest Nazi propagandists during WWII. All the while, he was working as an American spy... or I suppose agent would be a better word. Through coughs and slurs and mispronounciations he would deliver messages to American spies without his being aware of what it was he had delivered.

In the end he turns himself in, and the writing of his memoir takes place in a prison in Old Jerusalem while awaiting trial for war crimes.

Throughout the book, Campbell shows a slightly frightening sense of moral direction, in that he remains very aware of what he is doing and what he has done. Perhaps reading Adolf Eichmann's memoir (who Campbell encounters in prison) -- or even George W. Bush for that matter -- would be considerably different, and would paint the picture of a sociopath that would let any warm-blooded liberal sleep soundly at night, knowing there are insane people among us, and normal people don't do vicious things.

Well, Vonnegut shows things are not so simple, at least most of the time.

While listening to an old playback of his recordings in a neo-Nazi basement meeting, Campbell writes

I can hardly deny that I said them. All I can say is that I didn't believe them, that I knew full well what ignorant, destructive, obscenely jocular things I was saying.

The experience of sitting there in the dark, hearing the things I'd said, didn't shock me. It might be helpful in my defense to say that I broke into a cold sweat, or some such nonsense. But I've always known what I did. I've always been able to live with what I did. How? Through that simple and widespread boon to modern mankind--schizophrenia.

This truly isn't so different to what we all do, each on our own small scale.

This truly isn't so different to what we all do, each on our own small scale.We lament about the environmental crisis and sit in traffic for an hour on our way to work. We rail against poverty and child labour and buy Gap jeans. True, we haven't been gassing millions of innocent people, but I would bet it would have been hard to find anyone who believed that they were doing that, in those words. Even Eichmann claimed he was just following orders, stamping papers that came across his desk, despite being responsible for killing six million people.

The point I'm making is not to lift blame from any of these murderers, but to look at it in a slightly different light. Either our notion of responsibility + blame is skewed, or we are not as dissimilar in our motivations as these villains.

What a lot of this, and Mother Night, comes down to, is a matter of survival.

Campbell is an American play-write living in Nazi Germany and just like any other person, he is determined to survive. He certainly has a leg up on a ton of others in that he's already in Nazi society so he won't be shipped off to Auschwitz too quickly, but he still makes a decision to hop on the bandwagon, even if he doesn't believe in the direction it's going. The credit Campbell deserves -- why I don't see him as villain, really -- is that unlike many others, he doesn't bury his head in his knees as the bandwagon trundles along.

He remains standing, looking ahead, looking at himself, aware of what he's doing.

I have never seen a more sublime demonstration of the totalitarian mind, a mind which might be likened unto a system of gears whose teeth have been filed off at random. Such a snaggle-toothed thought machine, driven by a standard, or even substandard libido, whirls with the jerky, noisy, gaudy pointlessness of a cuckoo clock in Hell.Now, you may well ask, If a person murders, and is fully aware of what they are doing, does that make it okay?

The dismaying thing about the classic totalitarian mind is that any given gear, though mutilated, will have at its circumference unbroken sequences of teeth that are immaculately maintained, that are exquisitely machined.

The missing teeth, of course, are simple, obvious truths, truths available and comprehensible even to ten-year-olds, in most cases.

I have never tampered with a single tooth in my thought machine, such as it is. There are teeth missing, God knows -- some I was born without, teeth that will never grow. And other teeth have been stripped by the clutchless shifts of history--

But never have I willfully destroyed a tooth on a gear of my thinking machine. Never have I said to myself, "This fact I can do without."

You must congratulate yourself for having a very sharp mind if you asked this question. And of course, the answer to that question is No, that doesn't make it okay.

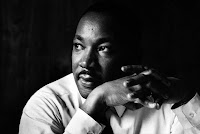

I'm sure James Earl Ray was very clear to himself about what he was doing when he pulled the trigger and shot Martin Luther King.

I'm sure James Earl Ray was very clear to himself about what he was doing when he pulled the trigger and shot Martin Luther King.The problem lies not in being clear about what you're doing, but about what Clarity is. Ray, that swine, I'm sure was very clear to himself and to his lawn-chair sitting, inbred, trailerpark neighbours, about what he was doing.

But a whole lot of us see things differently. We each have our own Clarity. Which Clarity is right? I can't say. Hopefully they overlap, and hopefully that overlap leans toward King and not Ray.

All I can say is to be very, very careful when accepting others' Clarities.

Campbell winds up getting bounced around, rescued in each case by some backroom bureaucratic American force. He wants a fair trial, and is beyond caring whether he's sentenced to death. He's searching for Justice, and he isn't even able to get that because it's still tainted by external, lopsided forces.

In the end, he makes the decision to hang himself. And that about sums it up: we are gravely mistaken in looking outward for truths. In the end, we each must make these decisions for ourselves, and can't rely upon others to make them for us.

She understood my illness immediately, that it was my world rather than myself that was diseased.Day after day, we all commit our minor, indirect, just-following-orders crimes, and we're continually let off the hook by society, by myopia, by the boon to modern mankind--schizophrenia. In the end, what we must realize is that until we do something as violent as murder another human, we'll keep getting let off for these little things because our collective notions of responsibility don't cover them.

Each of us needs to decide that our own actions have crossed a line, because for a lot of these little things, nobody else is going to.

We don't need to hang ourselves for our transgressions, but Campbell is able to show us that Real justice is a personal matter when it all boils down; not something to look outward for.

So those people on the bandwagon with their heads buried in their knees aren't far off the mark. They just need to stop looking at their crotch and start looking at their heart.

And on that, I'll let Campbell take us out...

I had hoped, as a broadcaster, to be merely ludicrous, but this is a hard world to be ludicrous in, with so many human beings so reluctant to laugh, so incapable of thought, so eager to believe and snarl and hate. So many people wanted to believe me!

Hey, nice site you have here! Keep up the excellent work!

ReplyDeleteSend Gifts to your Mother in Chennai